by Camilla Questa

… pay attention to a new regulation on the free flow of data

On May 28th the Regulation on a framework for the free flow of non-personal data (‘FFD’) in the European Union became applicable. The FFD regulation forms part of the Digital Single Market strategy, which aims -amongst others – at guaranteeing the free flow of data in the EU.

But what does this mean in practice? Thanks to this regulation companies are now free to store data anywhere in the EU, without unjustified national restrictions. This enhances competitivity of the data market in the Union and makes it easier for businesses to switch (cloud) service providers.

This new regulation complements the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), as together these two documents provide for the free movement of all data within the EU. The GDPR, besides raising the bar for the protection of personal data, it secures the free flow of personal data.

To avoid any confusions, the EU Commission published a guidance in which the interaction between the GDPR and the FFD regulation is clarified. Of major significance is the part focusing on the distinction between personal and non-personal data, and the regime applicable for the so-called mixed datasets i.e. datasets composed of both personal and non-personal data.

Personal vs. Non-person data

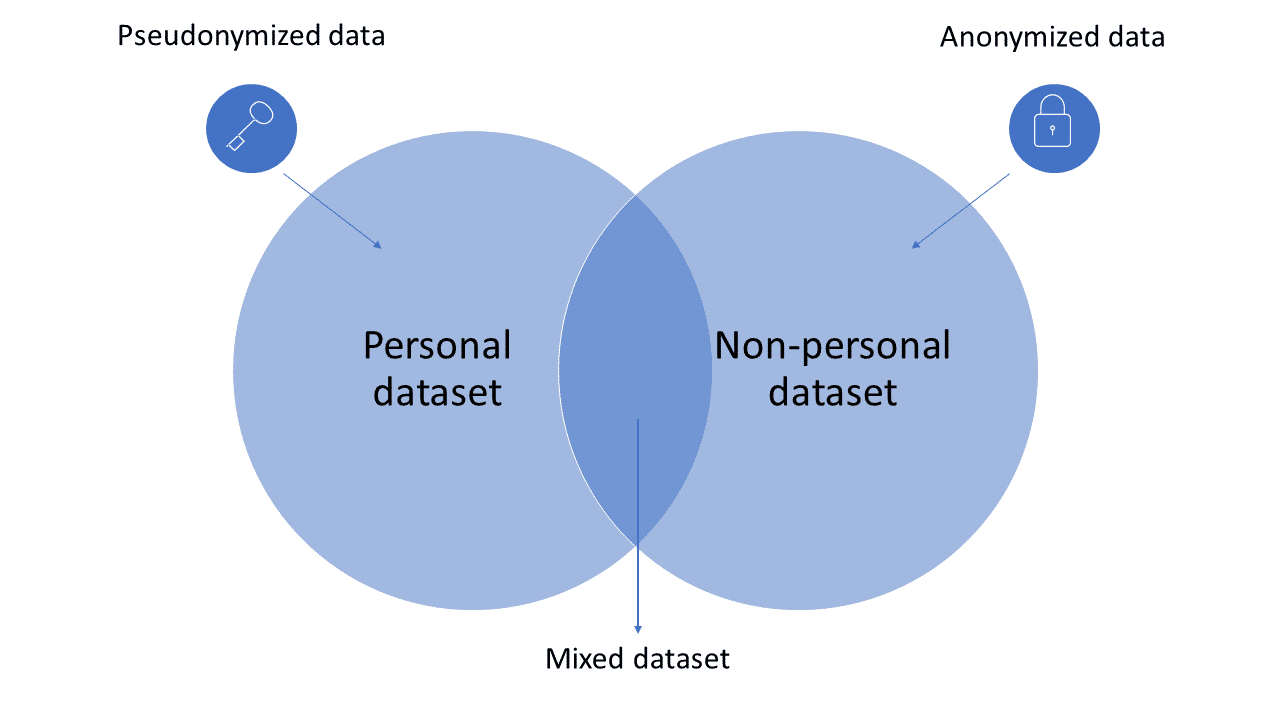

Personal vs. Non-person dataNon-personal data is identified as any other data that is not ‘personal data’ – as defined by the GDPR – and can be categorized based on its origin as:

- Data which initially did not relate to an identified or identifiable natural person. E.g. data on maintenance needs for industrial machines or trading data on the financial sector.

- Data which was originally personal data but was later anonymized.E.g. aggregated datasets used for big data analytics or anonymized data used for reporting purposes.

With regards to the second group of non-personal data, it is important to remember that anonymization differs from pseudonymization. Pseudonymized data is still considered personal data, as the information can be linked to an individual by combining it with additional data, and the GDPR rules apply to it. Instead, data that is correctly anonymized can no longer be attributed to a person, even when combining it with additional information.

The assessment of whether data is properly anonymized or not is not one-size-fits-all and depends on the circumstances of the specific case. As the Commission mentions in the guidance, if in any way non-personal data can be attributed to a person, and hence, making the person identifiable, the data must be considered personal and in scope of the GDPR.

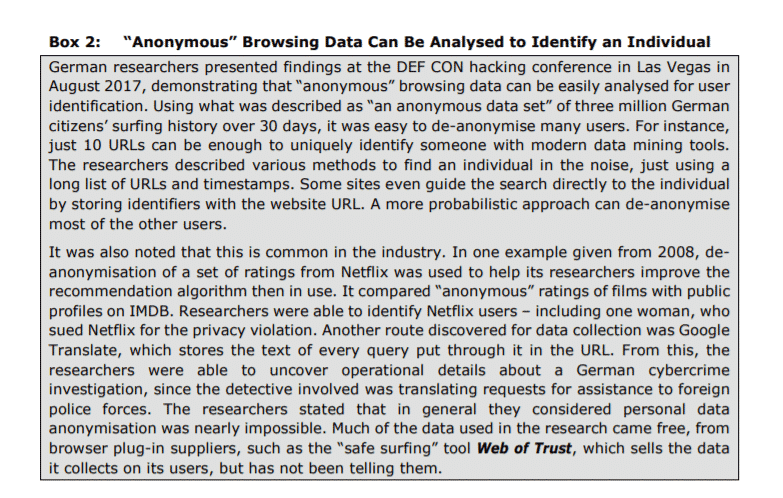

For example, it has been confirmed that “anonymous” browsing data can be analyzed to identify a user through a list of URLS and timestamps, or that is possible to identify authors of anonymous ratings by comparing these ratings with user profiles on other websites (see more on Figure 2).

Source – European Parliament’s ITRE Committee by Blackman, C., Forge, S.: Data Flows — Future Scenarios: In-Depth Analysis for the ITRE Committee, 2017, p. 22, Box 2

Mixed datasets

The process of de-anonymizing data to build individual profiles seems to be a new “trend”, as AI based algorithms allowing to mine personal data from non-personal data sets are developing and diffusing quickly. Besides, the increase in de-anonymization techniques, other technological advancements are blurring the distinction between personal and non-personal data, by generating a grey area of ‘mixed data’.

For example, let’s think about data stemming from smart cities: smart cities technologies are most likely associated to smartphone apps that allow the citizen/user to interface the smart city. Not only, smart cities models are based on connected devices acting as sensors, meaning that every object collects data which is then analyzed to improve the city’s objectives.

Consequently, IP or MAC address of citizens’ phone are also collected through those sensors and transferred to other devices via cloud technology. As a result, data generated through the smart city model can be used to track users, as well as to feed back into smart city initiatives.

Another example is the data contained in electronic health records or data collected from fitness apps. Here the distinction between personal and non-personal data is also blurred: besides individual sensitive data, aggregated health information can be inferred from user’s data and used for medical research or to improve treatments in the national health service.

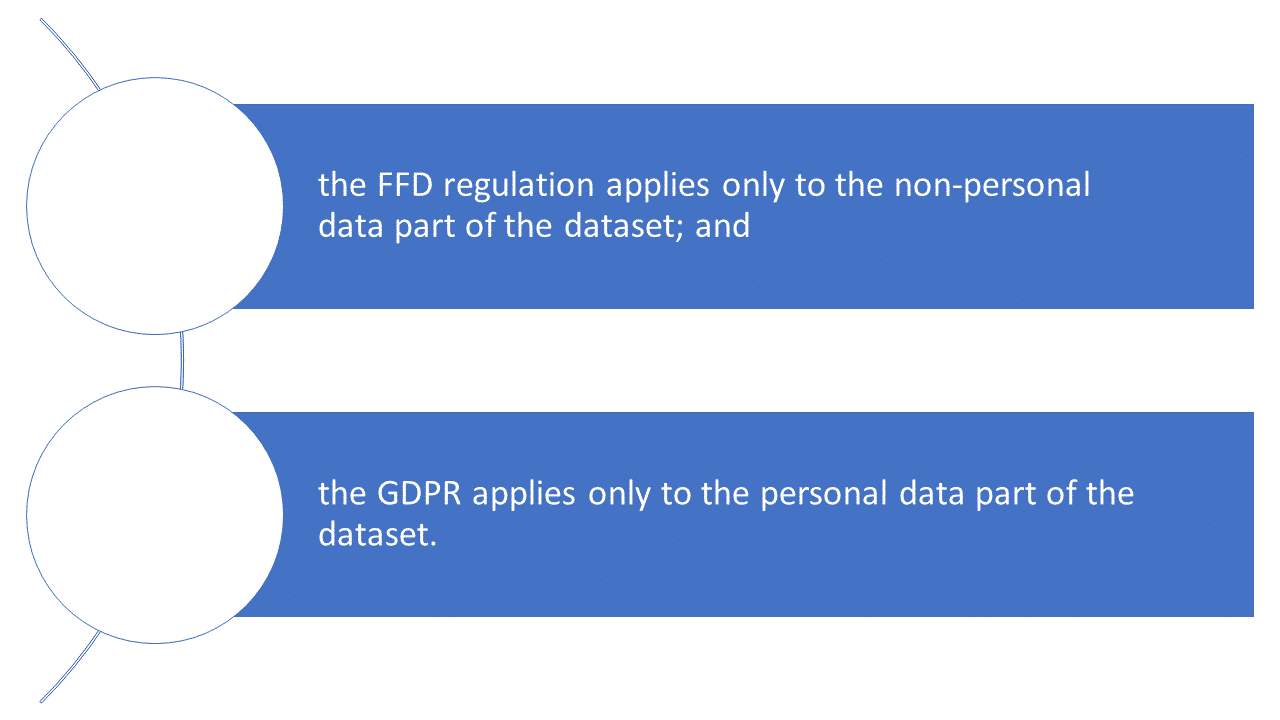

In its Guidance the Commission shed some light on the regulation of these mixed datasets. In the event of a dataset comprised of both personal and non-personal data:

Though, if in a mix dataset the non-personal data part and the personal data parts are inextricably linked, the GDPR applies to the whole set of mixed data, regardless of the amount of personal data contained in the dataset. In other words, if separating the set of personal data from the one of non-personal data is impossible, economically inefficient (e.g. if by separating the datasets, its value is compromised), or not technically feasible, the set of data shall be considered inextricably linked and the data protection rights and obligations stemming from the GDPR apply to the whole dataset.

Conclusion

As neither the GDPR nor the FFD regulation impose an obligation to separate personal data from non-personal data in a dataset, entities processing mixed dataset are free to choose if they want to separate the data or maintain the dataset mixed. If they choose the second option, they must apply the GDPR to the whole dataset.

However, given the developments in technologies that, on the one hand, are increasing the chances of de-anonymized non-personal data, and on the other hand, boosting the amount of mixed datasets, it seems that the application of the GDPR is designed to grow significantly. Moreover, if mixed dataset are processed by SMEs, it may be more convenient for these business to maintain the sets mixed and apply the higher standards of the GDPR to the entire data set. Considering that 99% of all business in EU are represented by small and medium sized companies, it seems even more likely that the standards of the GDPR will apply to the majority of datasets in the EU.

References

Kitchin, R. (2016) Getting smarter about smart cities: Improving data privacy and data security. Data Protection Unit, Department of the Taoiseach, Dublin, Ireland

COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL Guidance on the Regulation on a framework for the free flow of non-personal data in the European Union COM/2019/250 final

Forge S. (2018) Optimal Scope for Free Flow of Non-Personal Data in Europe

European Parliament’s ITRE Committee by Blackman, C., Forge, S.: Data Flows — Future Scenarios: In-Depth Analysis for the ITRE Committee, 2017, p. 22, Box 2